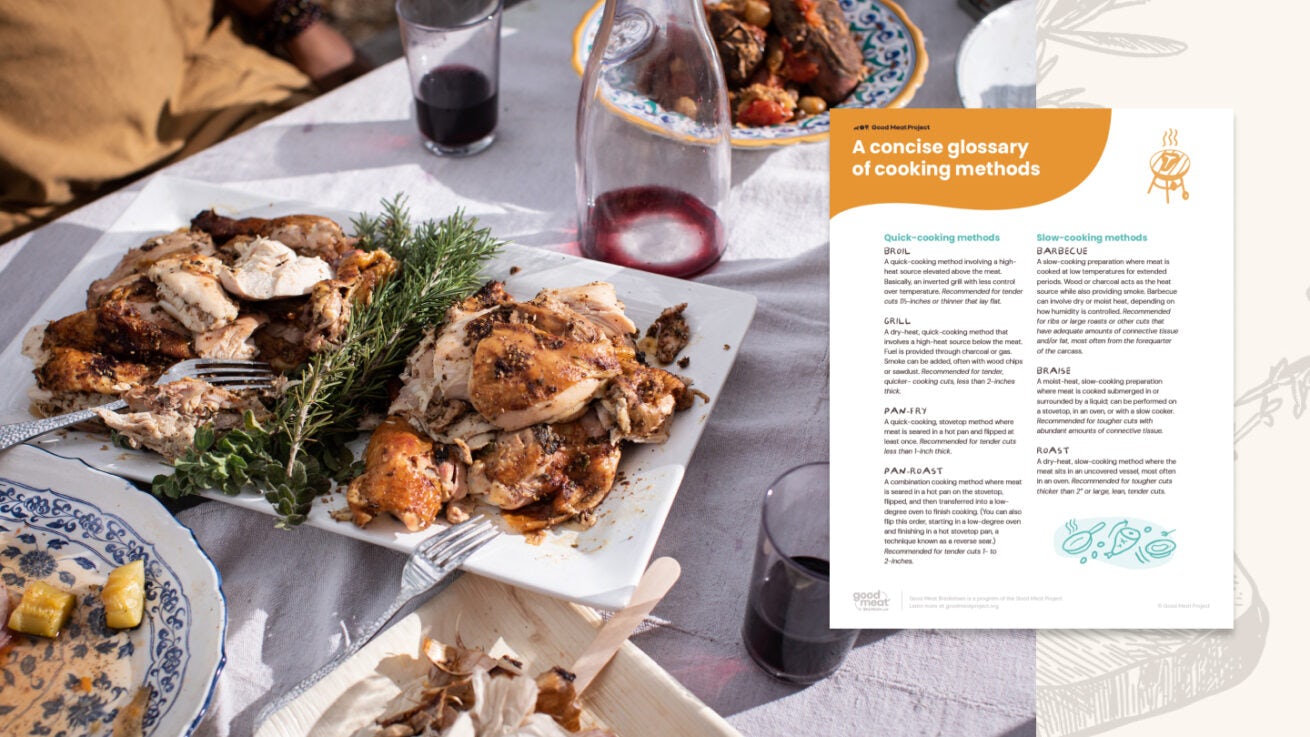

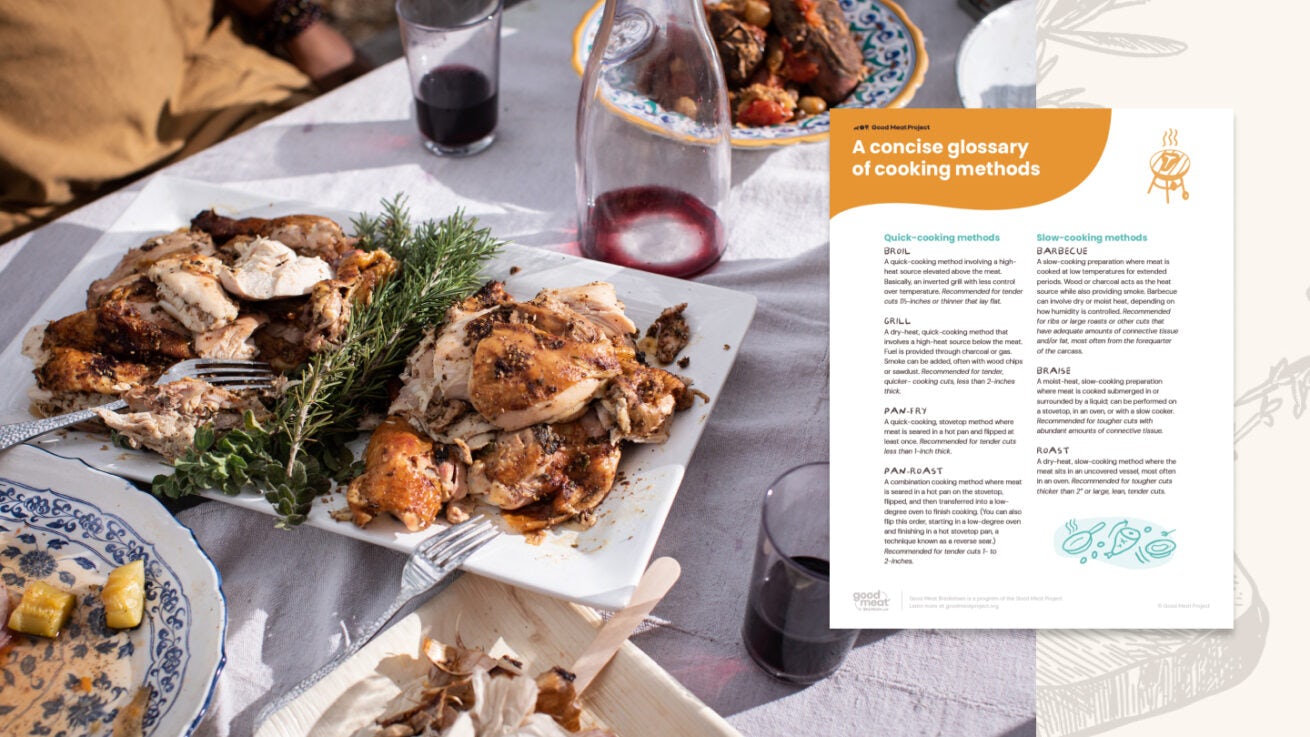

A concise glossary of cooking methods

This guide will help you select the appropriate cooking method for each cut of meat, no matter the species.

Good Meat BreakdownCookingChoosing and Cooking Cuts

Making your way through the various cut options you might encounter at a meat counter or when filling out your cut sheet for a bulk share, can feel a bit overwhelming. In the case of bulk buying, don’t hesitate to ask for guidance from the producer and the processor about the cuts and formats that will be the best fit for your eating habits. If you’re buying individual cuts from a butcher shop, start a conversation with your butcher.

But once you've got your meat in hand, what do you do with all the meat from your meat share or the cuts you came home with from your new butcher?

Fortunately, while the list of cut names and formats is lengthy, the methods for cooking them are far more succinct. In order to understand why different cuts cook in different ways, we must first understand a bit about the structure of meat.

We know that livestock animals move around on four legs, but it’s helpful to understand which areas of the animal work harder than others. Workload largely defines how you cook cuts from different parts of the animal’s body. In fact, you may want to get down on all fours yourself and move around a bit, taking notice of which parts of your body become quickly fatigued. (No, we have not installed a hidden camera in your house, so take as long as you like.) What’s true for cows is also true for pigs, sheep, deer, goat, and most four-legged animals, so this primer on muscle structure can be applied to any of the animals that end up on your plate.

The harder working muscles on an animal’s body, known as “high-working,” require more stamina and endurance than the muscles that have less to do (“low-working”). These high working areas include lower legs, areas of the shoulder, necks, rumps, tails, and cheeks. The muscles in those areas respond to the intense demands being made on them by offering more structural support in the form of higher concentrations of connective tissue, which helps them perform their tasks efficiently. The workload makes for more flavorful meat, but the structures in the muscles that support the workload make the meat less tender. But that is by no means a reason to give up on what we, in popular meat culture, tend to call “tough cuts.” When we get to cooking them, we’ll need to use methods that convert these tough structures to tender meat. Tough structure does not have to equal tough eating experiences.

The workload makes for more flavorful meat, but the structures in the muscles that support the workload make the meat less tender.

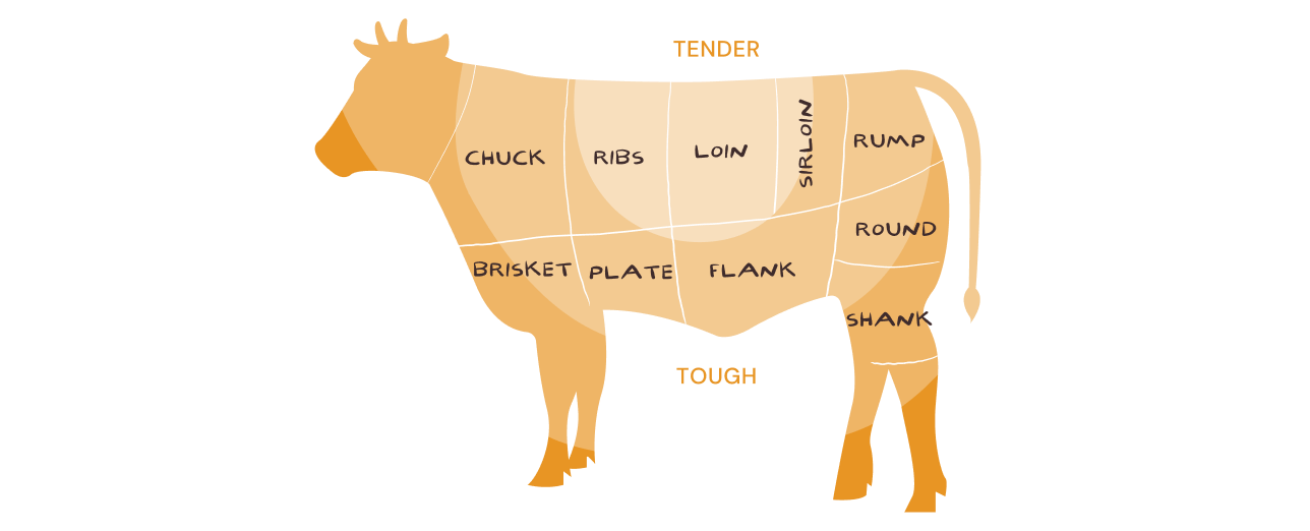

You may have noticed that the regions mentioned as high-working were largely lower areas (lower legs) as well as those in the front (shoulders, cheeks, necks) and rear (rump, tail) of the animal. This leaves the upper area as the largely low-working region: the middle and lower back, commonly known as the rib and loin region on most livestock. This is where your high-valued steaks come from, such as ribeye, t-bones, porterhouse, pork chops, lamb chops, tenderloins, and so on. Given the lighter workload on these muscles, the structure is more delicate and the flavor is less pronounced. Cooking these cuts doesn’t involve breaking down structures and increasing tenderness, as the cuts are inherently tender. They are easier and quicker to cook but that comes at a cost: less depth of flavor compared to higher working muscles. (Anyone comparing flavor in a beef tenderloin to a beef shank knows this stark difference.)

Knowing the general workload and structure of a muscle (and cut) will inform your choice of cooking method. That’s where those ubiquitous butcher charts can actually come in handy for eaters. Higher working areas of the carcass have stronger structures in place to meet the demands put on them. Thus, in order to fully enjoy the potential for flavor in these working-muscle cuts, we must utilize cooking methods that convert these tough structures to tender bites. Such cooking methods will include stewing, braising, smoking, roasting, and other slow-cooking approaches.

Conversely, low-working muscles give us tender steaks, chops, and thin cuts. Cooking with these cuts is about browning and bringing the meat to the desired temperature with quicker-cooking approaches that utilize high heat, such as pan-frying, pan-roasting, broiling, and grilling.

Why does this meat taste so….err…meaty?

Different aspects and variables of raising, harvesting, and cooking grassfed, pastured, or regeneratively-raised meat, for instance, contribute to its diversity of flavors. An animal's diet and lifestyle are huge determinants in the type and amount of fat the animal puts on and how its muscles build and form. How you cook your meat, to tenderize the muscle and release the fat, is another variable in how that meat is going to taste, when you finally get down to chewing.

There are three main factors that contribute to meat's flavor:

Humane slaughter practices also contribute to better flavor, as cortisol (the stress hormone), when released by the animal before or during slaughter, affects the taste and texture of meat. For those of us accustomed to eating meat that comes from young animals raised in confined animal feeding operations, who are fed the same kind of grain during much or all of their lives, the diverse, nuanced flavor of a 100% grassfed or pasture raised meat may surprise us at first. There’s a lot more science behind this than we’re letting on here, but for now we’ll just say, embrace that flavor!

This guide will help you select the appropriate cooking method for each cut of meat, no matter the species.

t’s good to bone up on your basic butcher lingo before heading into a shop. Here is a basic breakdown of meat case terminology.

What is tenderization and when should you do it?

Sign up for our newsletter. We’ll keep you informed and inspired with monthly updates.